Adventures on the flight of Horus 59 and beyond

Sunday February 25th 2023 saw the launch of the Horus 59 High Altitude Balloon by Project Horus, a group of electronics experimenters launching High Altitude Balloons in Adelaide, and part of the Amateur Radio Experimenters Group. A technical writeup of the days events can be found at the AREG blog here: Horus 59 Flight Report

Myself and a few other AREG members joined Mark, VK5QI for the planning stages of this flight, and with a very good flight prediction and weather forecasts for Auburn, near South Australia’s Clare Valley, on February the 25th, a launch was scheduled.

Getting there is half the journey

Living on the southern side of Adelaide, just the drive up to Auburn is a two hour affair. Leaving home around 7:30am, I first stopped for fuel and a check of tire pressure just before reaching the southern entrance to the South Road Superway, and had my first much needed coffee of the day. All the while having my Balloon Launch Day Playlist soundtracking my journey

Making quick time on the superway, northern connector, and finally northern expressway I emerged from the northern suburbs of Adelaide, stopping for coffee #2 and breakfast in roseworthy, at the beginnings of the Horrocks Highway.

I would learn sometime after this trip, courtesy of the excellent ‘;DROP TABLE Adventures;– That the Horrocks Highway is named for John Horrocks, an explorer and pastoralist from the early days of English settlement in South Australia. While on an expedition near Lake Torrens in 1846, Horrocks was fatally shot when his own camel accidentally discharged his shotgun while he was reloading it.

Continuing north, it’s not long before the highway begins snaking its way over rolling farmland.

Continuing past Tarlee, I diverged onto the Barrier Highway at Giles Corner, passing through Saddleworth before finally arriving at Auburn Oval, where launch preparations were already underway.

Pre-Launch

Arriving at Auburn oval, a small team consisting of Mark VK5QI, Liam VK5ALG, Will VK5AHV, and Ady VK5FADE had already begun the launch preparations, with assembly of the payload train underway – the attaching each of the five payloads to the line that would be carried by the balloon.

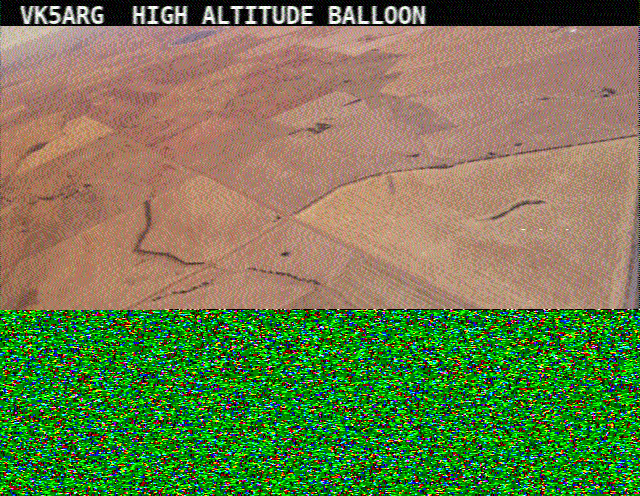

The payloads on this flight consisted of two Horus Binary telemetry units, one sending weather data and the other geiger counter measurements, in addition to their position data, as well as Liam’s LoRA tracking payload, Wenet high speed digital imagery payload, and slow scan TV analogue imagery payload.

After briefly saying hello to everyone, I proceeded to setup my car based receivers for position and imagery reception. I had equipped my car with three receivers, two RTL-SDRs for Horus Binary and Wenet reception, along with my Yaesu FT-818 for SSTV, with the former both feeding a Raspberry Pi 4 running horusdemodlib, chasemapper, and wenet receiver, with the chasemapper interface being accessed from a small tablet mounted to the windscreen.

As telemetry began streaming into my receiver from the two positioning payloads, the balloon team had begun the filling process.

As filling was completed and tie-off began, the two imagery payloads were also switched on, and imagery began streaming into our receivers as well, capturing the final stages of the launch preparation

Launch!

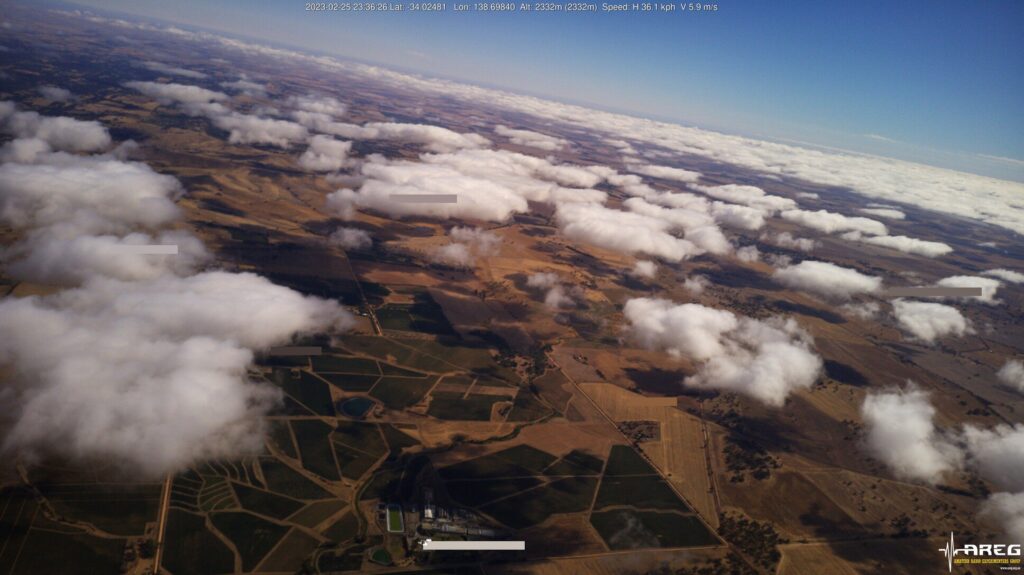

Before long, the balloon train had been raised into the air and was released, ascending almost perfectly vertically. With the flight predicted to neatly follow the nearby Barrier Highway north, enter into an ‘S’ pattern as it passed through the various layers of wind in the stratosphere, before bursting and following the Barrier Highway again towards its landing site, the launch team had the opportunity to wait for a short time and watch some of the images received from the balloon

The Chase

With the balloon now well in the air, the chase teams departed, with a goal to rendezvous at a rest-stop on the side of the Barrier Highway at Hanson, where Peter VK5KX had setup his ground receiving station.

Passing through remote farmland as we made our way up the barrier highway, we finally arrived in Hanson to wait out the later stages of the balloon ascent until it finally burst. By this time, the flight path had shifted slightly, with the balloon predicted to pass almost directly above us.

With the balloon almost overhead, and with almost a complete lack of cloud directly overhead, we began searching the sky for sight of the balloon. It had reached ~30 kilometres altitude at this point, where the low pressure outside had caused the balloon to expand massivlely, out to ~15 metres wide. Coupled with the reflective nature of the its surface, it is visible to the naked eye with some hunting.

Beginning by focusing your eyes on the clouds at the horizon, you then look immediately up, searching for something that looks like a faint star in the daytime. Using this technique, several of us were able to watch the balloon in the final stages of its ascent up to ~32km before it burst, which appeared stunningly to us on the ground that the balloon appeared to vanish in a puff of smoke.

The Descent

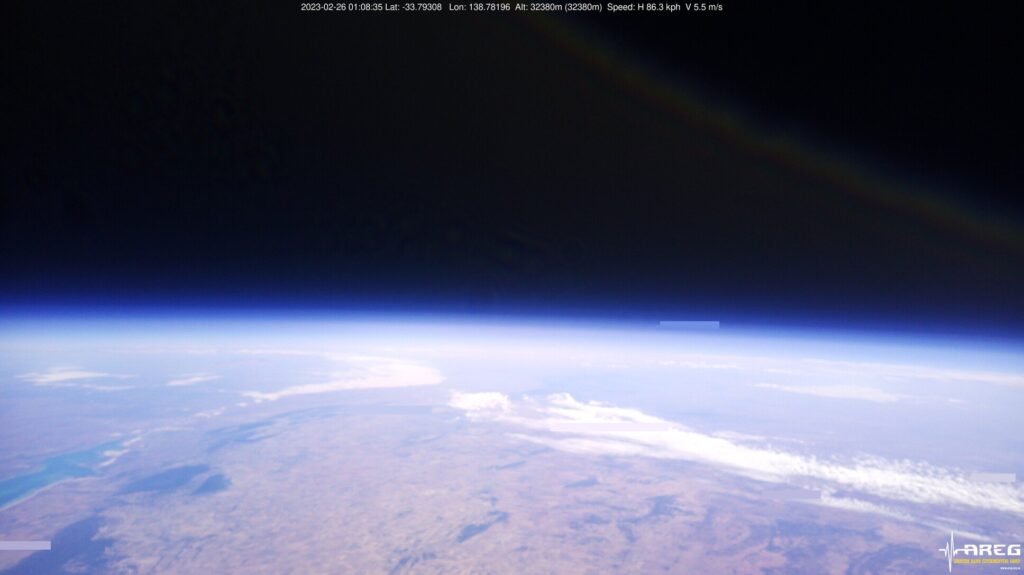

After reaching a peak altitude of 32,813 metres, the balloon burst and our payloads began rapidly falling back to earth. During this time, they were still being pushed along at 40-50 KM/h, but with the predicted landing site only a few kilometers away, we stayed at our location in Hanson for a while longer, waiting for the landing predictions to become more clear so that we could drive to meet the landing payloads directly.

Continuing to watch the received imagery as we waited, we received a clear photo taken moments before burst at 32,380m. Looking out over the Mid North of South Australia, we can see the top of the Spencer Gulf in the lower left, with the city of Port Augusta at its inland tip

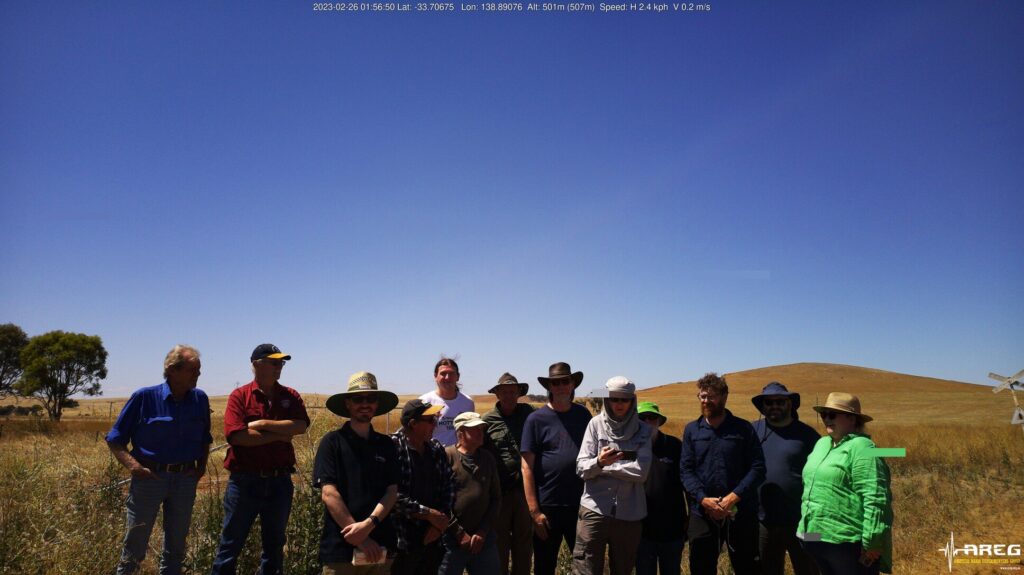

The chase teams then finally made their way north, stopping on the side of the Barrier Highway adjeacent some fields that the predictions were beginning to close in on.

Shortly afterwards, we watched the payloads descend on their parachute, and the team ventured a short distance into the field to collect them, wrapping the chase up nicely with a group photo taken by one of the payloads

Heading Further North – Burra

Having never visited the town of Burra, a few kilometers for the north, I said farewell to the rest of the chase team, who had decided to head back to Adelaide via a bakery in Seven Hill.

Proceeding on, I reached Burra, a town of just over one thousand people in South Australia’s mid north. The area where the town is located today had been used for sheep grazing for a few years prior to 1845, with the town developing rapidly from that point, after copper was discovered in the area by a local shepherd.

The town takes its name from the Burra Burra creek that runs through it. This name was initially given to the Burra Burra copper mine, with the group of small townships surrounding the mine becoming collectively known as ‘The Burra’. These townships remained disparate until 1940, when they were consolidated into a singular town bearing the name Burra.

The township is dotted with historic buildings from the days of mining, and in 2017 the entire town was placed onto the National Heritage Register, becoming the only town on the list. This is largely due to the importance of the town not only for the history of the local area, but for the history of South Australia as a whole, with some crediting its mine as saving the colonial government of South Australia from bankruptcy.

Burra Burra Mine

After spending some time looking around the southern part of the town, and getting some lunch from the local Waters Bakery, I proceeded north, following the Barrier Highway further up to the former site of the Burra Burra copper mine. Upon entering the site, the mine lookout road climbs sharply up to a peak overlooking both the mine and the township below.

From the mine’s opening in 1845, through to 1867, mining was carried out using the traditional method of cutting underground shafts and tunnels, reaching a tunnel depth of 187 metres by 1867. In 1870, operations switched to the revolutionary open cut method, becoming the first open-cut mine in Australia. By 1877 the open cut had reached a depth of 37 metres. This proved to be unprofitable, and the mine would close shortly after.

In its 32 years of operation the mine had produced 50,000 tonnes of copper metal from the 700,000 tonnes of ore excavated, and at its peak was was the largest copper mine mine in Australia, producing 5% of the world’s copper between 1850 and 1860

The mine would remain dormant for 94 years until further mining operations began in 1971, continuing for a decade. In this time, the depth of the pit would reach 100 metres, with only 24,000 tonnes of copper metal being produced from 2 million tonnes of ore. Mining operations would cease in 1981 after the exhaustion of the remaining ore.

Looking back towards the town, you can easily make out the tree lined Burra Burra creek as it snakes through the valley below. Visible by the roadside at the entrance to the mine is Peacocks’s Chimney which originally served as a boiler chimney for one of the sites engine houses. The expansion of the mine in the 1970s required it be demolished, but recognising its historical value, volunteers from the National Trust of South Australia painstakingly dismantled the tower and rebuilt it in its current location.

Looking back around to the northwest at the lookout, you can also see the wind farm on Hallett Hill in the distance

Next, I joined the walking trail through the open air museum, containing the remnants of the industrial activity that once surrounded the mine pit.

A few hundred metres walk from the carpark you reach the dressing tower, which once contained a series of crushers and sieves that would break apart the ore and concentrate the ore particles for collection.

A small tramway was used to carry the ore from the point where it left the mine, to the top of the two storey dressing tower. From there if would be dropped into a hopper and be fed by gravity through crushing rollers and sorting sieves, before being placed into Jigging separation machines which separated concentrated ore particles from the waste material.

From there, I made my way up the hill to the chimney used by the crusher engine, before making my way back down to Morphett’s enginehouse, a three storey building that formerly held the Cornish made Beam Engines that were used for water pumping and haulage for the underground tunneling operations at the site.

Morphett’s enginehouse was restored in the mid 1980s after the mine closed for the second time, and today serves as the site museum. To gain access the enginehouse to view the museum collection, as well as a number of the additional mine ruins on the western face of the pit, a key from the local visitor centre down in the township is required. Regrettably, I didn’t stop in at the visitor centre to get the key, so wasn’t able to continue exploring the mine site, and made the short walk from the enginehouse back to the carpark.

Burra Railway Station

From the Mine, I made my way down to the railway satation on the northern edge of town.

Burra Railway Station opened in 1870 as the terminus of the Burra railway line, the second railway line built running north of Adelaide, opening just ten years after the extension of the Gawler Line to Kapunda. The line would then be extended north from Burra over the next decade, reaching Terowie in 1880, Before a separate narrow gauge line was run from Terowie to Peterborough to join with the line to Broken Hill.

Passenger services ran to Burra up until they were cancelled in 1986, with the line north of Burra being closed and removed between 1988 and 1993. The last grain trains ran to Burra in 1999. The line was technically never closed and is still leased by freight operator Aurizon, however several sections of the line have fallen into disrepair, making operating trains here impossible in the current day.

The former station building has been lovingly restored in recent years by the Friends of Burra Railway Station, who have reopened the building as a museum/bed and breakfast. Sadly, with the museum closing at 1pm, I was too late to look inside, but took some time to view the information displays on the outside of the station building.

Looking back at the station from the other side of the line, we get a better view of the ED22 "Edie" dining car, also being restored by the Friends of Burra Railway Station. Built by Commonwealth Railways as part of their ‘D’ Class dining car fleet, this carriage entered service in 1917 before twice being converted for other uses in the 50s and 60s before finally being stored in a poor state in 1987.

Midnight Oil house

Departing the railway station, I rejoined the Barrier Highway to once again head north for a few kilometers more to Cobb & Co. corner, which is the site of what may be the most famous abandoned farmhouse anywhere.

Built in the 1920s before being left to ruin sometime in the following six decades, the house is best known for its place on the album artwork for Australian band Midnight Oil’s 1987 album ‘Diesel and Dust’, a photograph captured by photographer Ken Duncan while exploring the region in the 1980s. The building is best known today as ‘The Midnight Oil House’.

This location is also reasonably close to Hallett Hill Wind Farm, offering a better view of the turbines that I first saw back at the mine.

Highway to the End of the World

Departing from the Midnight Oil house, I made the short journey back into Burra, by which time it was 4:30 and I was starting to feel a little sluggish. With 200km still to cover over the course of more then two and a half hours, I decided to stop and get some snacks before getting on the road again.

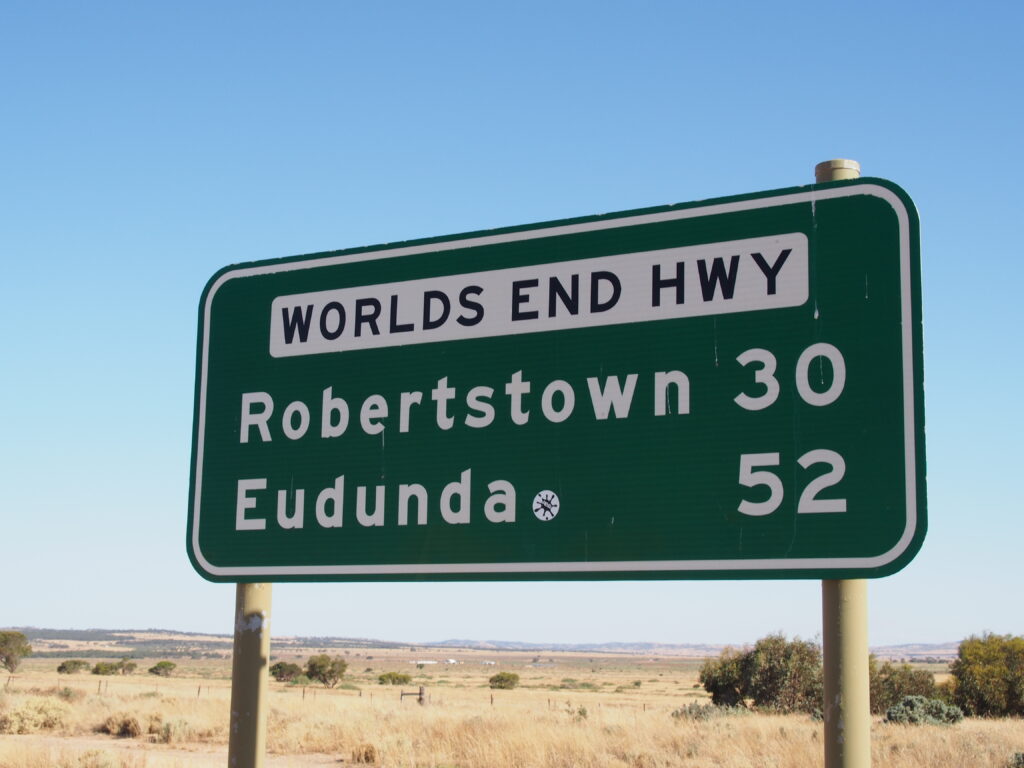

Looking at a map of the area before my trip, something special caught my eye. Lying to the east of the Burra Hills south of the town was the wonderfully named ‘Worlds End Highway’ that departed from the Goyder Highway slightly east of Burra, making its way south to Eudunda, via the locality of Worlds End, South Australia. With the route being only 15km longer than simply retracing my path down the Barrier Highway, detouring this way was an easy choice to make.

Leaving Burra on the Goyder Highway, it isn’t long until the view opens up beyond the range, across a wide expanse of flat country towards the Riverland, with the highway signage showing that I was indeed closer to Renmark (only just) than I was to home.

Not long after departing Burra, we reach the Goyder Highway’s junction with the Worlds End Highway. There’s a small parking area near the corner that provides a view down over the floodplain that the World’s End Highway traverses.

Descending down to the floodplain, you really start to get a sense of why the area is referred to like it’s the end of the world. It feels empty here, with the highway running through in more or less a directly straight line, and little sign of people residing out here.

After driving for a short time, I reached the locality of Worlds End itself. With a population of just fourteen people at the 2021 census, there really isn’t a lot going on. There used to be more here, from 1876 to 1971 the area had a post office, from 1889 to 1975 an active methodist church, and from 1888 to 1944 even had a school. Today only the church building remains, abandoned and overgrown.

The weather was very pleasant out here, as it had been for much of the day. With a small amount of mobile coverage here, the BOM app was able to give me the exact temperature at The End of the World.

Alas, I wouldn’t stay long, not far from the church was some roadkill that had been baking in the higher temperatures seen earlier in the day, clouding the immediate vicinity with a foul smell. Getting back into the car, I proceeded south once more.

Homeward Bound

Departing Worlds End, I departed for the final two and a half hour drive back to Adelaide, and to home. Traversing the rest of the highway to Eudunda, I stopped briefly to stretch my legs, taking a short walk to view the silo art at Eudunda’s disused railway station.

Eudunda station was opened in 1878 with the opening of the Gawler-Morgan railway line, an extension of the Gawler-Kapunda line that had opened in 1860. Trains ran to Morgan up until 1969 when the line past Eudunda closed, making it the new terminus. Trains to Eudunda continued until 1994, when the section of the line from Kapunda to Eudunda was closed, with deteriorating condition of bridges on the line being given as reason for closure.

The grain silos at Eudunda are still in use today, with grain being transported by truck instead of rail.

Departing Eudunda on the Thiele Highway I began the final stretch of my journey home, travelling through towns in the Barossa Valley before arriving back at the northern expressway. From there, I retraced my path back to the south of Adelaide finally arriving home at around 8:30pm, for a total of 13 hours of adventuring, spanning 440km.

It was a long day for sure, but was a fantastic adventure, both in getting to experience a high altitude balloon chase in person, and in getting to explore a new part of South Australia and make some fun memories!